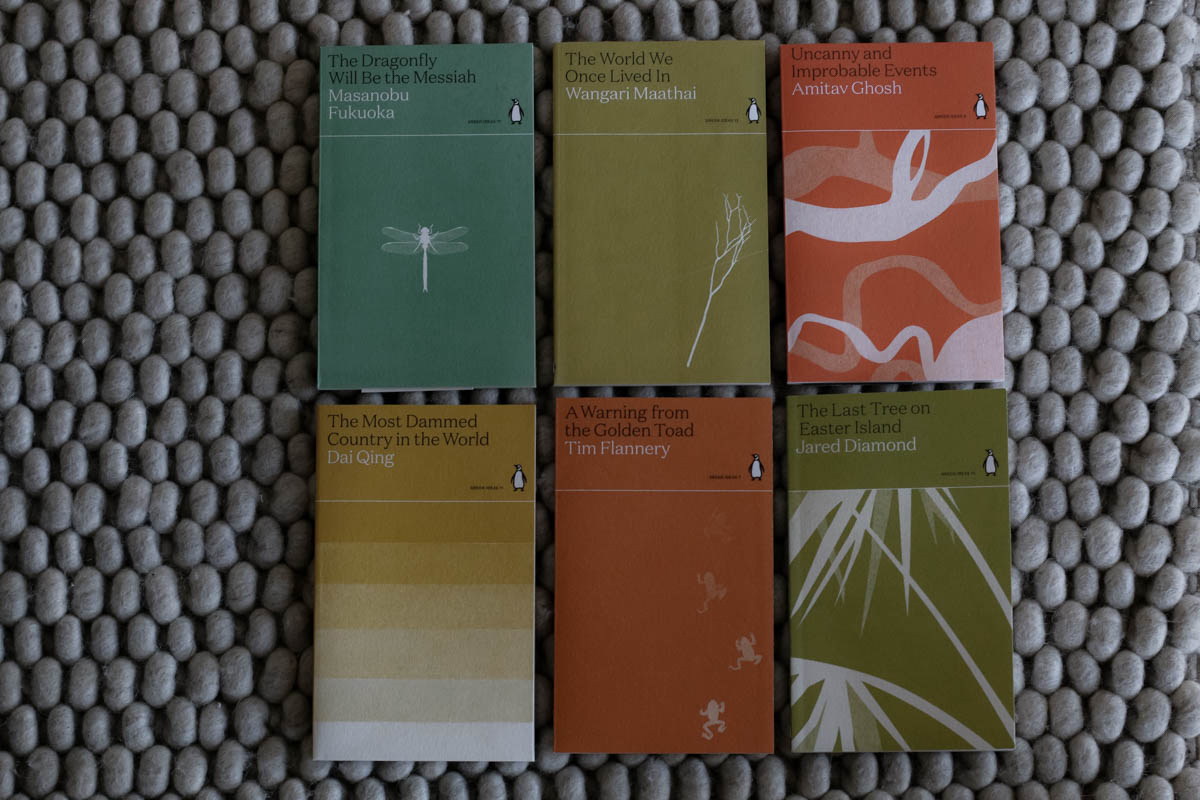

In 2021, Penguin Books launched an awesome new series called Green Ideas.

Green Ideas contains 20 short books by “visionary thinkers around the world who have raised their voices to defend the planet”. These writings are widely regarded as the classics of the environmental movement.

My favorite thing about the series is its diversity. Besides authors, like Rachel Carlson, who’s known for penning the first globally influential environmental book, Silent Spring or Jared Diamond, whose books are widely read all over the world, it also includes less mainstream (for lack of a better world) thinkers, like Wangari Maathai or Masanobu Fukuoka. Their non-Western experience constitute an invaluable addition to how we think about nature, the climate crisis, environmental justice, and our place and responsibility in this world.

The books are usually on average 70-100 pages long, so can be read in under 2 hours. They are collections of essays, writings, or extracted from longer works so they are great for getting a taste of that author’s style and thoughts.

Below, you can find some short reviews of the 9 works I’ve read from the series so far. I tried to mix authors whose books I’ve already read to see how the shorter versions fare up to their longer works, with others whom I’ve never read (or even heard about). Some I personally found more interesting or engaging than others, but I don’t think you can make a mistake by choosing either one of the series. You’ll learn something new from each and every one of them.

Wangari Maathai: The World We Once Lived In

Wangari Maathai was a Kenyan social, environmental, and political activist and the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Price for her “contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace”. She founded the Green Belt Movement in 1977, an indigenous, grassroots organizations to promote environmental conservation; build climate resilience, and empower communities, especially women and girls. The Green Belt Movement to date has planted more than 50 million trees in Kenya. In her writings, she explores the sacred power as well as the ecological and spiritual importance of trees, and why we, humans, destroy the forests that keep our bodies and souls alive.

I really liked this one – in the first part, she makes a case for why trees are so important and why we shouldn’t treat them as a commodity that can be exploited endlessly. The second part looks at how different cultures, religions, and communities honored trees and forests throughout history and the important spiritual role they played in traditions and mythologies.

But underlying our host’s comment was a worldview that’s all too common: that there are always more trees to be cut, more land to be utilized, more fish to be caught, more water to dam or tap, and more minerals to be mined or prospected for. It’s this attitude towards the earth, that it has unlimited capacity, and the valuing of resources for what they can buy, not what they do, that has created so many of the deep ecological wounds visible across the world.

Wangari Maathai: The World We Once Lived In

Naomi Klein: Hot Money

Naomi Klein is a Canadian author, filmmaker, and activist and one of the most well-known and influential commentators on climate change and climate justice.

Klein is one of the authors whose work fundamentally shaped my political and social views. She is an ardent critic of capitalism and corporate globalization and can lay down the problems and the path to solution in an easily understandable way. If you wanna understand how capitalism and corporate globalization led to the current environmental and social crisis, read This Changes Everything: Climate vs Capitalism. She manages to lay down complex economic and social issues in a very understandable way and provides practical solutions and policy recommendations as well. Or you can start with this little book, Hot Money, as this is kind of a shorter summary of her most important arguments.

Because what is overwhelming about the climate challenge is that it requires breaking so many rules at once – rules written into national laws and trade agreements, as well as powerful unwritten rules that tell us that no government can increase taxes and stay in power, or say no to major investments no matter how damaging, or plan to gradually contract those parts of our economies that endanger us all.

Naomi Klein: Hot Money

Bill McKibben: An Idea Can Go Extinct

Bill McKibben is one of the most well-known environmental activists in the world. His classic book, The End of Nature (1989) was one of the earliest summaries of the ecological disaster we have created and the first book that was written on global warming for the general audience.

Similarly to Klein’s Hot Money, this short book is basically a summary of his main arguments presented in The End of Nature – that by changing the earth’s entire atmosphere, the weather, and the most basic forces around us, we are effectively ending nature. It’s a good introduction to McKibben’s thoughts, and I think it will make you wanna read The End of Nature as well (which I really recommend).

We have changed the atmosphere, and thus we are changing the weather. By changing the weather, we make every spot on earth man-made and artificial. We have deprived nature of its independence, and that is fatal to its meaning. Nature’s independence is its meaning, without it there is nothing but us.

Bill McKibben: An Idea Can Go Extinct

Terry Tempest Williams: The Clan of One-Breasted Women

Terry Tempest Williams is an American author, conservationist and activist. In her writings she advocates for social and environmental justice, ecological consciousness , the protection of public lands and wildness, and social change.

This book was one of my favorites in the series – mostly because her writing is very eloquent and beautiful. The essays cover different topics, from the impact of nuclear testing (her family lived near a nuclear testing site in Utah and she believes exposure to radiation is the reason so many members of her family have been affected by cancer) to the importance of environmental legislation (through concrete stories of successful protection campaigns) and a call for reflective activism.

The Wilderness Act of 1964 has not changed, we have. We read the landscape of our lives differently. Our connection to the world is virtual, not real. An apple is not just a fruit but a computer. A mouse is not simply a rodent but a controlling mechanism for a cursor. We have moved ourselves from the outdoors to the indoors. Nature is no longer a force but source of images for our screensavers. We sit. We stare. We text on our iPhones and type on our keyboards, and await an immediate response. Patience is an endangered species. Intimacy is a threatened landscape.

Terry Tempest Williams: The Clan of One-Breasted Women

Dai Qing: The Most Dammed Country in the World

Dai Qing is a Chinese activist and journalist who has been campaigning against the Three Gorges Dam since the 1980s. She is currently forbidden to publish or speak publicly in China but remains there to continue documenting the truth about the regime.

The Most Dammed Country in the World is a series of essays mostly about the construction and the related environmental problems of the Three Gorges dam, the largest power station of the world. Because this is a collection of writings and speeches, it is a bit repetitive sometimes and is very much focused on the concrete issue of the dam. In the introductions she talks more generally about the human and environmental cost of China’s rapid rise and would have liked to read more about that.

As the old Chinese adage says: ‘Things will develop in the opposite direction when they become extreme’ (wuji bifan). This is the case with our current socialist regime and its blind faith that engineers and technical fixes can solve all problems. The result of all this is uncontrolled development, and there is no better symbol of uncontrolled development than the Three Gorges dam.

Dai Qing: The Most Dammed Country in the World

Masanobu Fukuoka: The Dragonfly Will Be the Messiah

Masanobu Fukuoka was a Japanese farmer and philosopher who inspired sustainable, organic practices with his approach to natural farming and the revegetation of desertified land.

In the book, Fukuoka reflects on the global economic trauma, what kind of mistakes led here, and how we can heal the earth. He argues that we should appreciate all diverse forms of nature – e.g. there are no more, or less useful plants, higher or lower life forms. Nature is one body, and everything has a role in the grand scheme of things. At the end of the book, he also shares his experience in using natural methods to revegetate soil and create a thriving, natural farm.

There is no good or bad among the life-forms on earth. Each has its role, is necessary, and has equal value. This idea may seem simplistic and unscientific, but it is the basis for my plan to regenerate landscape all over the world.

Masanobu Fukuoka: The Dragonfly Will Be the Messiah

Jared Diamond: The Last Tree on Easter Island

Jared Diamond is an American geographer and historian, who’s mostly known for his transdisciplinary nonfiction books about human societies (he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his influential book, Guns, Germs, and Steel).

The Last Tree on Easter Island was another one of my favorites – it takes us to the remote Easter Islands, famous, of course, for its mysterious gigantic sculptures (and yes, the book does provide theories for how they were constructed). The place’s history is fascinating – as Diamond shows, it was one of the first civilizations that has basically destroyed itself by exploiting its own natural resources. It’s a super interesting story, and a timely warning to us.

The Easter Islanders’ isolation probably also explains why I have found that their collapse, more than the collapse of any other pre-industrial society, haunts my readers and students. The parallels between Easter Island and the whole modern world are chillingly obvious.

Jared Diamond: The Last Tree on Easter Island

Tim Flannery: A Warning from the Golden Toad

Tim Flannery is a paleontologist, scientist, and one of Australia’s leading writers on climate change who has discovered more than 30 mammal species.

His short essays cover crucial climate change problems around the world – the destructions caused by burning fossil fuels, how the coral reefs got to the brink of collapse, the extinction of the golden toad, how the warming of Antarctica endangers its animal population, what are the major climate tipping points that, when exceeded, lead to irreversible changes. It’s a bit different to the other books in the series in that it’s a lot more scientific in tone and style.

The golden toad is the first documented victim of global warming. We killed it with our reckless use of coal-fired electricity and our huge cars, just as surely as if we had flattened its forest with bulldozers.

Tim Flannery: A Warning from the Golden Toad

Amitav Ghosh: Uncanny and Improbable Events

Amitav Ghosh is an award-winning Indian novelist and critic whose works have illuminated the shortcomings of prevailing cultural narratives about the climate crisis.

This short book explores a really intriguing and though-provoking question – why does contemporary culture, and especially literary fiction find it so hard to deal with climate crisis? Even though it is undoubtedly the most defining issue of our times, it is mostly addressed in nonfiction form. Why does the modern novel and our collective imaginations fail to grasp the severity of the climate crisis?

Indeed, it could even be said that fiction that deals with climate change is almost by definition not of the kind that is taken seriously by serious literary journals: the mere mention of the subject is often enough to relegate a novel or a short story to the genre of science fiction. It is as though in literary imagination climate change were somehow akin to extraterrestrials or interplanetary travel.

Amitav Ghosh: Uncanny and Improbable Events